| News | |

| QuikScat | |

| NSCAT | |

| YSCAT | |

| SAR Research | |

| SCP | |

| CERS | |

| Publications | |

| Software | |

| Studies | |

| Lab Resources | |

| Group Members | |

| Related Links | |

| Contact Us | |

| Getting to BYU | |

Passive CubeSats for Remote Inspection of Space VehiclesIn 2003, the Space Shuttle Columbia fractured into pieces amongst attempting an emergency reentry into Earth’s atmosphere, and the crew and vehicle were lost. A hole had developed in the wing of the shuttle due to a piece of foam insulation that broke off from the external tank and hit the wing, and in an attempt to save the vessel and it’s passengers, NASA instructed the crew to return to Earth. However, the heat from reentry penetrated the interior systems through the hole in the wing, and ruined many critical systems, including the control system. This led to the destruction of the Space Shuttle Columbia, a vessel who flew 27 times successfully beforehand. The ultimate conclusion of the accident report was that if Columbia had simply remained in space, another space shuttle could have met up with Columbia and, at the very least, the crew could have been saved. There were several methods of inspection that Columbia could’ve done, but due to either unpreparedness or expense, they were not. To prevent any future tragedies similar to Columbia, a way to remotely inspect vehicles in space was needed, and CubeSat are ideal for filling that need. Currently, there are many ways to remotely inspect a space vehicle, which are listed below along with their pros and cons.

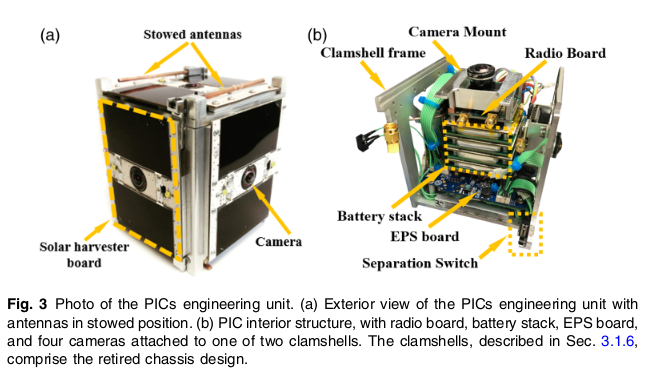

BYU’s Passive Inspection CubeSat (PICs) offers a powerful alternative to the above inspections in many cases. Because PICs is passive, the inspection risk is low. With its 360 degree by 180 degree spherical camera system, the coverage is very good, and the resolution can be good depending on the separation tumble. Depending on how it’s used, the CubeSat can respond quickly, and it is low cost. The PICs CubeSat chassis is made up of 6 interlocking walls. On the outside of the chassis, there are solar panels on the four long sides. On top there are 2 stowed antennas. Within the chassis, there are batteries, the radio, the EPS board, the Separation Switch, and the cameras, which stick out of the chassis to record the footage. An image of the CubeSat can be seen in Fig. 3. Furthermore, as CubeSat is used in space, it will get better in both price and performance, and further uses can be explored. For example, one potential future use is by changing it so that the cubesat relays not to the ground but to the parent satellite, it could greatly reduce the amount of time that it needs to be on. Therefore, the size and price could be greatly decreased. As the CubeSat is used, it will only get better.

For more information, please visit here. Reference: Patrick Walton, Josh Cannon, Brian Damitz, Tyler Downs, Dallon Glick, Jacob Holtom, Nicholas Kohls, Alex Laraway, Iggy Matheson, Jason Redding, Cory Robinson, Jared Ryan, Niall Stoddard, Jacob Willis, Karl Warnick, Michael Wirthlin, Doran Wilde, Brian D. Iverson, David Long, “Passive CubeSats for remote inspection of space vehicles,” J. Appl. Remote Sens. 13(3), 032505 (2019), doi: 10.1117/1.JRS.13.032505. |